-

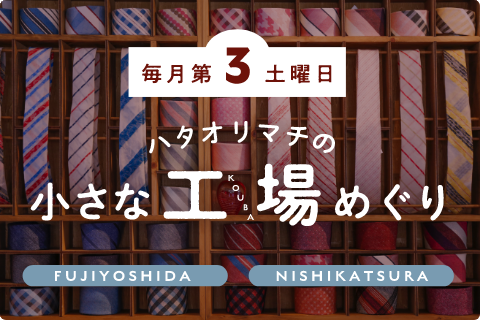

I’ll show you around

Old monkey

Old monkey

A millennium-long tradition of textile production

(1)The beginning of Yamanashi textiles “the legend of Jofuku

Yamanashi textile production has existed for 1000 years, but legend places its origin back yet another 1000 years. It is said that during the Qin Dynasty, a court sorcerer named Jofuku traveled to Japan by boat from China in search of an herbal remedy that promised eternal life that was said to grow on “Mt. Horai at the farthest end of the eastern sea.” The peak he sought turned out to be Mt. Fuji, known at the time as a mountain of immortality. He searched in vain for the mythical herb to no avail. The legend goes that Jofuku, unable to return to his homeland, married a local maiden and taught weaving to the local townspeople, and from there the town became well-known for its weaving. To the extent that there remain, to this day, shrines dedicated to the veneration of textiles as gods, the ties between Yamanashi textiles and Jofuku run deep.

-

It’s said that Jofuku last emerged as a crane (TSURU means cranes in Japanese) at the end. That’s why historically this region was called TSURU-GUN.

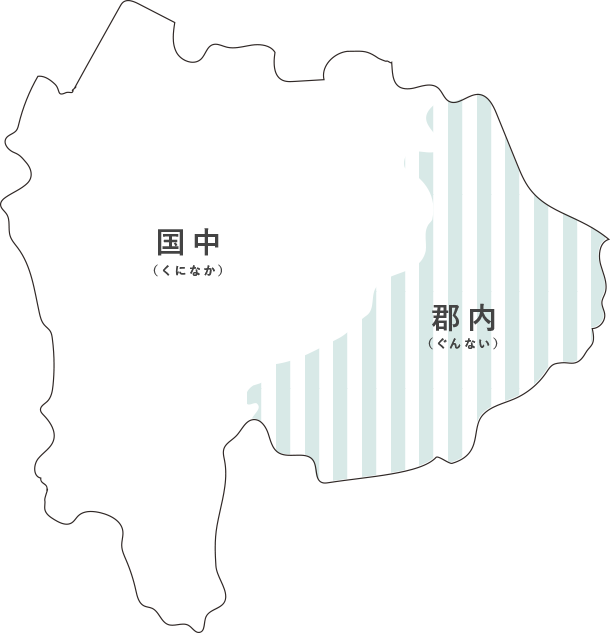

(2)The people who have woven a thousand-year history

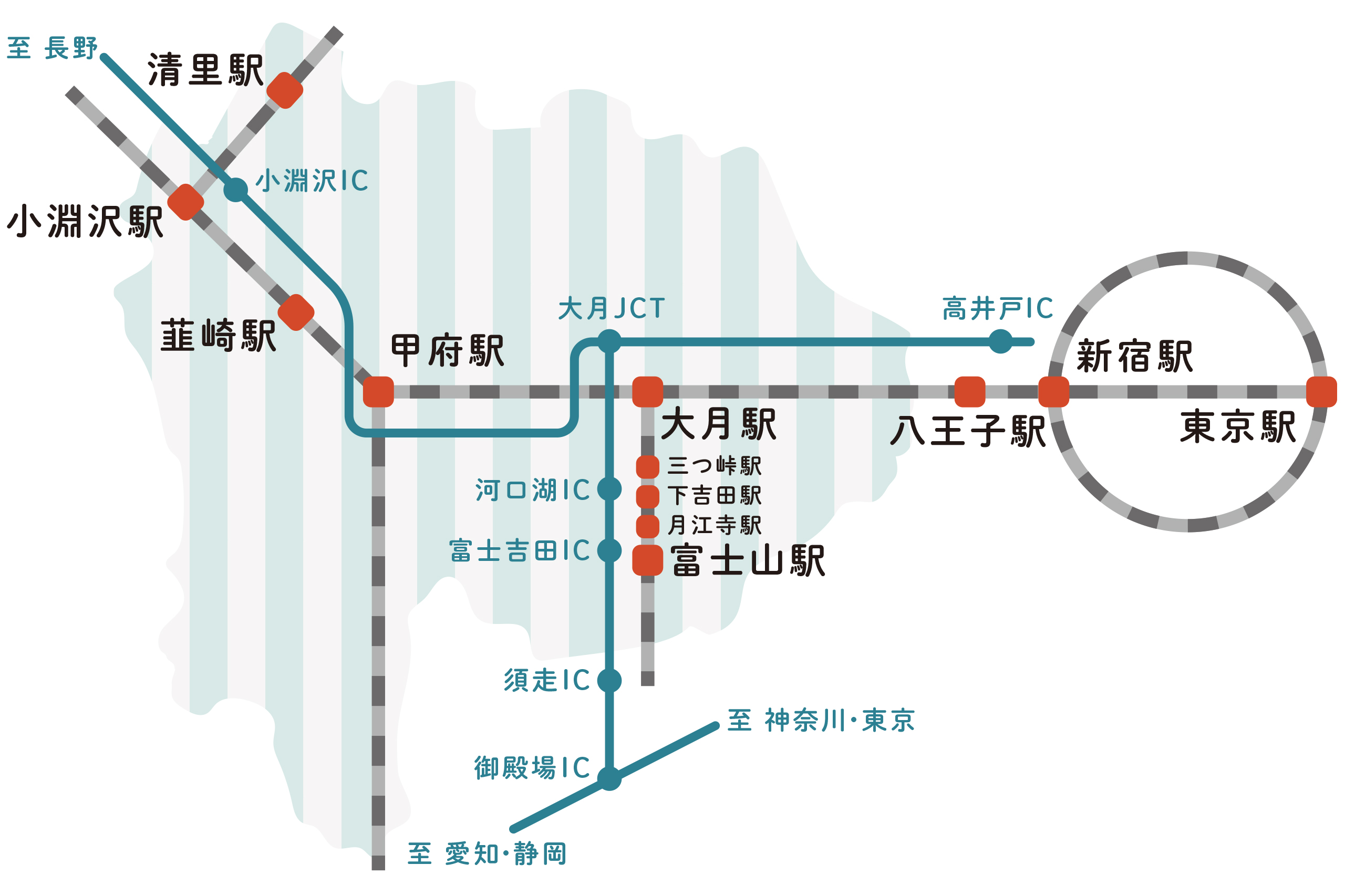

Yamanashi textiles made their earliest known appearance in documents from 1000 years ago, during the Heian Era. The sentence “Kai (the original name for Yamanashi) is to supply fabric” can be found in the “Engishiki” a text from the Heian Era that detailed the laws and customs of the time. Regions with a history of production extending back as far as 1000 years are rare even in a country like Japan with a comparatively long history on a global scale. Fujiyoshida City and neighboring Nishikatsura Town are part of the larger “Gunnai” region, and textiles produced in this area are widely known as “Gunnai Orimono” (Gunnai textiles) or “Kaiki” (Kai silk).

-

1000 years is 40 generations of ancestors ago. Perhaps we’ve continued for so long thanks to being watched over by Mt. Fuji

The beautiful, extravagant textiles that mesmerized the masses during the Edo Period

(1)The luxurious fabrics that “styled” Tokyoites

Throughout the Edo Period, laws were passed prohibiting extravagance of any form, permitting samurai and townspeople to wear clothing made only with approved materials and colors. However, “edokko” (Tokyoites) would express their style by using luxurious materials in the hidden lining of their clothing. Flashy colors and elegant fabrics that were otherwise prohibited were used as lining and allowed individuals a sense of luxury.

This is where Gunnai textiles make their debut! Due both to the quality of color and fabric, both of which were very much to the stylish taste of “edokko,” and the region’s proximity to Edo (present day Tokyo), Gunnai textiles came to be highly favored and widely used. Kai silk was commonly used as the lining of “haori” (traditional formal coats).

Kaiki silk lining

Kaiki silk lining Ultrathin, hidden Kaiki silk lining

Ultrathin, hidden Kaiki silk lining

(2)The textile region that everyone knows

During this period, the Gunnai region, acclaimed throughout the Edo (present day Tokyo) region for its superior weaving technology, was thought to be the epicenter of textile production. It was even said that Kyoto textiles could not compare to Gunnai textiles. From their appearance in the classic works of notable cultural and literary figures of the time such as Natsume Soseki, Chikamatsu Monzaemon, Ihara Saikaku, it is apparent that Gunnai textiles and Kai silk were once common household names.

-

""粋 IKI(Chic)” means stylish but playful. "粋 IKI(Chic)” is to pay particular attention to details even in places that are not immediately visible

The rapid manufacturing boom of the Meiji Period

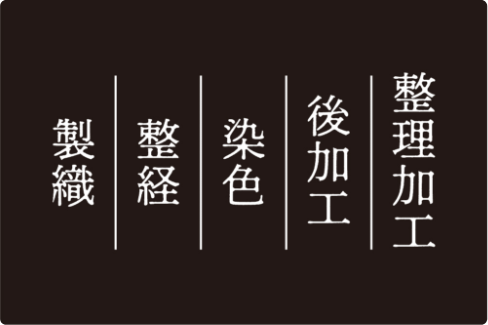

(1)The craftsmanship of Kai silk

Kai silk, which was widely produced from the Edo Period through the beginning of the Showa Period, is known for being particularly light, soft and luminous. Because Kai silk production does not utilize the typical technique of twisting thread to increase density, interwoven threads are characteristically thin, with 42 denier vertical strands, and 52 denier horizontal strands. The horizontal strands were woven in at a density of 200 to 280 strands per 3.03 centimeters, requiring incredible skill. The young woman in the poem “Futatsu no Kobako (Two Small Boxes)” by female poet Misuzu Kaneko, is depicted as having treasured her kai silk and kept it safe in her treasure chest.

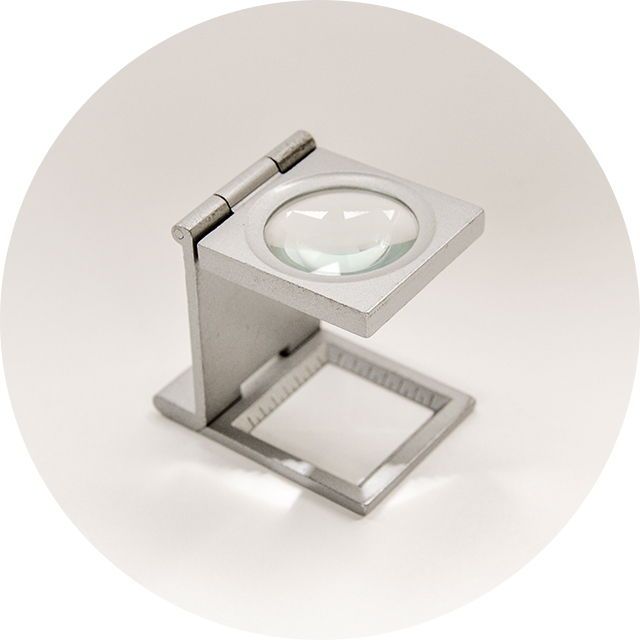

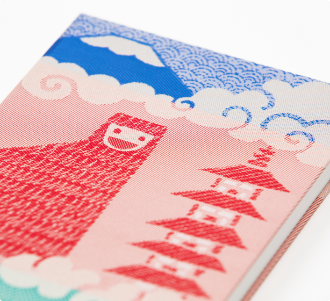

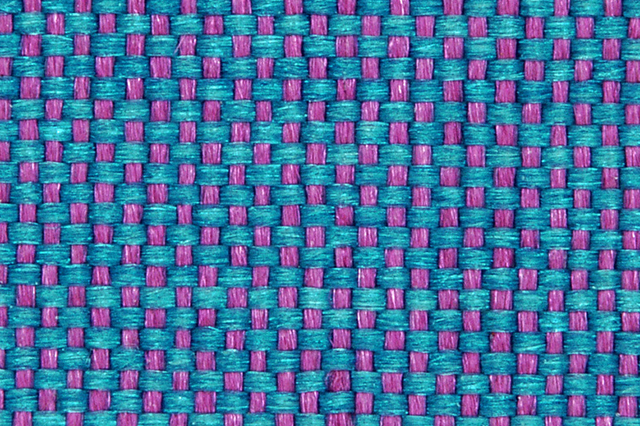

Intricate images created by weaving

Intricate images created by weaving A magnified image of high density weaving

A magnified image of high density weaving

(2)The era that weaving was stolen

From the outset of the Showa Period and the start of the war, manufacturing industries throughout the country began to struggle. Roughly 9,300 of the looms used in textile production throughout the country were seized for use as metal during the war, rendering textile manufacturers unable to continue production. Wartime items such as military parachutes continued to be made, but the production of goods for profit rapidly declined.

(3)The Golden “Gatcha-man” Era

Following the war, when production could resume freely, this region began producing fabric in unprecedented volumes. This period was known as the “Gatcha-man” era, named this way by playing on “gatcha” the sound that a loom makes and “man” the counter for quantities of 10,000 in Japanese, meaning that one stroke of the loom would guarantee the sale of 10,000 yen worth of sales. The mass textile production that occurred during this time led to a labor shortage and necessitated the hiring of large numbers of women known as “ori-hime.” The new use of synthetic fibers also yielded more durable materials than before.

-

Many people rose from hardship to create textiles “gatchaman” has a funny ring to it doesn’t it

(4)The rise of the “Nishiura” Area and local cuisine

As the textile industry saw more and more success, so too did local drinking establishments. Silk shops lined the eastern side of Honcho Street earning this area the name “Kinuyamachi” (silk shop town). On any day of the month with a 1 or a 6, this area would transform into a marketplace where merchants from all over the country would come to negotiate sales, and in the evening would enjoy the nightlife of the bustling “Nishiura” area.

As the textile industry saw more and more success, so too did local drinking establishments. Silk shops lined the eastern side of Honcho Street earning this area the name “Kinuyamachi” (silk shop town). On any day of the month with a 1 or a 6, this area would transform into a marketplace where merchants from all over the country would come to negotiate sales, and in the evening would enjoy the nightlife of the bustling “Nishiura” area.

Yoshida udon, also known for horse meat toppings

Yoshida udon, also known for horse meat toppings “Gatcha-man” era

“Gatcha-man” era

The impact of foreign trade

(1)The battle between foreign products and the Yamanashi textile industry

Approaching the end of the Showa Era, cheap foreign textiles became widely circulated. Though the Yamanashi textile industry had tried to modernize little by little, many were unable to keep up with the competition, consequently leading to many of the local textile manufacturers going out of business.

(2)The destruction of household looms

It was against this backdrop that the Yamanashi textile industry took its hardest blow that caused irreparable damage. Due to trade friction with exports to the United States, the country attempted to revise manufacturing practices, and enacted a widespread buy up of unused looms. During this period, a staggering 40% of the looms found in family factories, considered a part of each weaving household of Yamanashi textile industry, were destroyed, and the sound of looms at work disappeared one by one

Images of looms being destroyed

Images of looms being destroyed Views of silk town

Views of silk town

-

In this way, one by one people stopped weaving It must have been so sad to part ways with looms that had become like family members

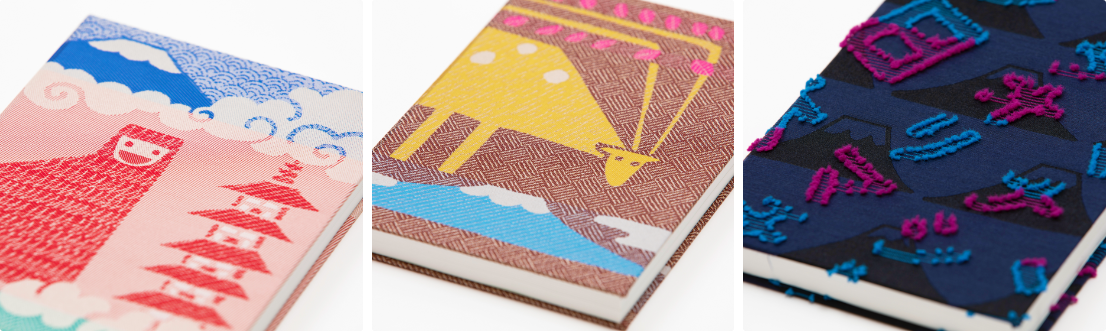

The birth of a new factory brand

(1)The new “hataya” factories

Those who felt the impending crisis of the decline of the industry were the second and third generation successors of the factories. Understanding that the production of such delicate threads into high-density fabrics is a rare feat, they were determined to offer their prized fabrics not only to other luxury brands but also as a brand in and of itself.

(2)An industry woven together

Textile factory workers are true craftsmen. Bringing production to its fullest potential necessitated the collaborative efforts of countless individuals. By thinking up new products, creating new designs, and strategizing about different uses and marketing, the industry slowly began to make a name for itself yet again. What you see lined in the shops today are the product of the collective efforts of not only the craftsmen of the factories, but also of weavers, marketers, designers, the Yamanashi Prefecture Industrial Technology Center, the students of Tokyo Zokei University, administrators and industry supporters. The factories of the Yamanashi textile industry continue to weave their beloved fabrics at the northern base of Mt. Fuji today.

-

They’ve reclaimed themselves as a name recognized by any and all as a textile industry that’s inherited superior technique. Hataya are taking more pride and paying even more attention than ever on their textiles